A Florida condominium’s deadly collapse could force stunned engineers and architects, homeowners associations and local officials to address questions about whether they’ve done enough to maintain other decades-old buildings — and who should foot the bill for more frequent inspections and improvements.

“I don’t think anyone in the structural engineering community saw this type of tragedy coming. I think all of us are reeling from it, and saying, ‘Wow, there is definitely something to be learned here,’” said Anne Cope, the chief engineer for the Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety. “This is a moment like Katrina and like Andrew, where we are going to learn something and make changes.”

South Florida’s building codes, experts said, are among the nation’s strongest — designed to keep residents safe from hurricanes. The state implemented mandatory codes after Hurricane Andrew ripped homes from their foundations and left 65 dead in 1992, and some counties have added more stringent requirements.

But many of the region’s buildings were constructed before 1992, including Champlain Towers South, which was built in 1981 as part of a South Florida condo boom. Those buildings are subject to the codes that were in place at the time of their construction, and are only required to undergo inspections every 40 years — such as the 2018 review of the Surfside, Florida, condo in which an engineer raised red flags that the building was beginning to address, but did not warn of imminent disaster.

At least 11 people have died after the building crumbled on June 24th, and rescue crews are racing to find the 150 still missing. The condo’s collapse has also raised questions about whether older buildings have undergone the repairs they need — and, if not, who will pay for them.

Those questions apply outside South Florida, too. Environmental threats have led to building code changes across the United States in recent decades. California overhauled its requirements in hopes of protecting residents from earthquakes, and the federal government began playing an active role in building codes following the San Fernando Valley earthquake of 1971 that leveled several buildings at a Veterans Administration hospital. Louisiana implemented building codes in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Elsewhere, tornadoes, rising sea levels, overflowing rivers and other environmental threats have forced changes to building codes.

Other states have not adapted, instead leaving it to municipal governments to set building codes. Texas and Mississippi did not follow Louisiana’s lead after Katrina and other hurricanes in recent years, opting to allow counties to determine their own rules.

The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety has rated the states along what it calls the “hurricane coast” — Atlantic and Gulf Coast states in the United States. Florida, Virginia and South Carolina ranked at the top of the organization’s list. Texas, Alabama, Mississippi and Delaware fell to the bottom. But regardless of building codes, complete structural failures like the one in Surfside are exceedingly rare in the United States.

“Buildings just don’t fall down like this,” said Norma Jean Mattei, a professor at the University of New Orleans and former president of the American Society of Civil Engineers. “I can’t wrap my arms around, what could have been the actual, initial failure mechanism that caused the collapse.”

Mattei said building codes across the United States since 2000 have been largely built on the model International Building Code. Within the code are references to additional model codes on materials such as steel and concrete and on design loads.

“Codes are updated after natural disasters, as well as after engineers identify changing conditions, such as more frequent hurricanes or materials’ erosion along coastal regions,” Mattei said,

But, because the materials and designs used in construction have changed over decades, it’s not reasonable to force the owners of buildings constructed before modern codes were adapted to meet those codes.

“So you’ve got to figure out how you can think of how you can make people safe and keep people safe, but not have standards so onerous that their financial health is at risk,” Mattei said.

Some buildings could need more immediate repairs — potentially at impossibly high price tags for those who live there to pay. That raises questions about whether governments are willing to partially foot the bill as part of the country’s broader infrastructure obligations.

There are no clear answers yet on why the Surfside condominium tower crashed to the ground, but early signs point to some failure in the lower reaches of the 13-story building, perhaps in its foundation, columns or underground parking garage.

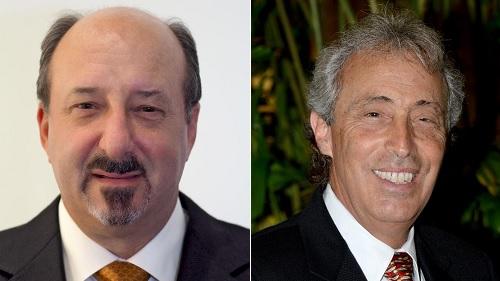

“An immediate step that homeowners’ associations should be required to take involves mandating the collection of high enough fees to replace crucial elements such as roofs by the end of their life expectancy,” said David Haber, the managing partner of Haber Law, a construction and real estate firm in South Florida. “Condos’ homeowners association should be prohibited from tapping into money collected for those purposes to use instead on cosmetic upgrades such as improved lobbies. And they should not be allowed to waive those fees’ collection to keep prices low to compete against nearby condos. You’re putting boards in situations of having to choose between making their lobby look nice for sale purposes versus having a property that’s not corroding. We have to even the playing field and make it where the boards don’t have the discretion to waive life safety reserves. The problem is, people do not think beyond the immediate future. And they certainly do not think beyond their life expectancy. You’re never going to get unit owners to vote to pay more money. So you have to have less discretion on the board level of a volunteer board. It has to be, ‘Well we don’t have a choice.’ ”

Others said local governments need to mandate more frequent inspections and force buildings to address problems raised in those inspections.

“What we’re trying to encourage our local leaders to do is to make sure that they have an exhaustive process that monitors not only the step of construction and remodeling for buildings but also makes sure that we do everything possible to have a comprehensive inspection program,” said Clarence Anthony, the executive director of the National League of Cities and the former mayor of South Bay, Florida. “We’re trying to help our municipal leaders come up with ways so that this won’t happen again.”